To introduce the topic of the Radif of Persian music and the Dastgah system we will look at a scale that was introduced into Persian music quite recently by one of the most renowned Iranian Tar players Hossein Alizadeh. His scale is his own creation. It is the combination of two preexisting melodic niches of Persian music: Daad from Mahur, and Bidaad from Homayoun. It is called Daad o Bidaad. The ‘o’ here means ‘and’.

Mahur in Persian music is most similar to the major scale in western music. It can be played in any key but it is usually played in the Key of C. So the tonic of the scale is C. As we discussed in this article, the Radif is a collection of melodies that develops the modal character of each Dastgah. In the Radif of Mirza Abdollah, Mahur has 44 different niche (gushe) melodies that develop the degrees in the scale. One of these niches is called “Daad”, which literally means “call”, or “roar”. The connection between the meaning of this word and the melody itself is not clear, it could refer to lyrics in a poem that was historically sung with this melody, or it could be something even more historically obscure. For example, in another Dastgah called Bayat-e Tork, there is a gushe (niche) called “Jame Daran”, which means, “clothes rendering”. This name may refer to an old tale about a famous court musician named Nakisa who played with such passion and such a beautiful melody that everyone went mad and tore off their clothes (what happened next, I will not speculate on).

This is the introduction to Mahur the grand scale to which Daad is a part of:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/116477169″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

This is the melody that characterizes Daad:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/116477513″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

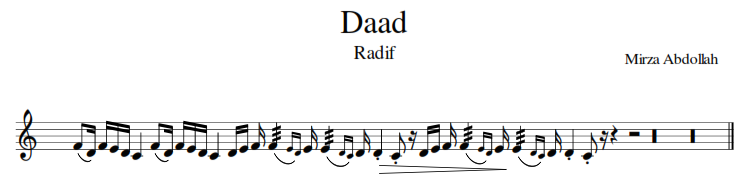

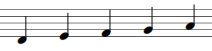

Below is a short transcription of Daad from Mirza Abdollah’s Radif:

As you can see and hear Daad is using the 2nd degree and 4th degree of the scale to create its melody. The melody starts on D, frequently pauses on F, and resolves on D, which creates a modal effect when playing Mahur because Mahur usually resolves on C. This clearly demonstrates the modal character of Middle Eastern music. It also shows that the modes and gushes don’t require a full scale of 7 notes to make it complete.

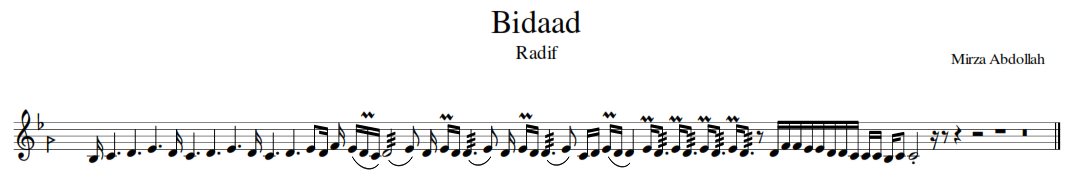

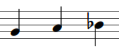

Now let’s see how Bidaad relates to this. Bidaad is a gushe in the dastgah of Homayoun. Homayoun is a Persian scale that resembles in some ways the harmonic minor scale in western music. It is also closely related to both Nakriz and Hijaz found in Arabic music.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/117100076″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

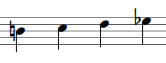

As you can see the note that is common to both Daad and Bidaad is D. The focal point of the gushe Bidaad is D, and the starting note of Daad is D. This allows for modulation to occur between the gushe Daad and Bidaad after resolution of the melodic development. Now let’s here what the two sound like after a maqam is created to merge the two gushe together. This is played by me but this was composed by Hossein Alizadeh.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/116634858″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Melodic Development of Daad o Bidaad

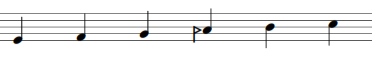

This was semi-improvised and copied from what Hossein Alizadeh plays on his album Raze No. The melodic development begins on D which is the common root of both Daad and Bidaad. The first melody to be developed is in Daad, which uses D E F G A and returns to D. The creative aspect that Alizadeh introduces here is how he moves to bidaad. He pauses on E natural, and then returns to D while playing an E flat which creates the bidaad effect. After introducing the E flat, you can move down to B natural, and develop bidaad which primarily uses B C D Eb F with the melodies gravitating toward D. In the daramad, Bidaad is introduces very briefly, and then goes to another part of Mahur. This is characterized by starting on D and playing the fifth interval which is A natural. This is an improvised melody that uses the upper range of Mahur which uses B flat after A natural. The notes used in this upper trichord are G A Bb C, which is in essence the ajna Ushaq.

(I noticed that this is exactly the same interval as Ushaq/Busalik tetrachord. In fact, there is a gushe in Dastgah of Nava which is called Ushaq in which it is characterized by developing the same interval of notes but transposed to C D Eb F with D being the focus of the melody. I noted this for those interested in comparing Persian and Arabic music. In Persian music, Ushaq is a sub-mode or ajna of dastgah Nava.)

So the tonic(shahed in Farsi) or root of the scale is D which is also the common root of both Daad and Bidaad. The second most important note in the scale is F natural, which establishes Daad borrowed from Dastgah Mahur. The third most important note is A which can be used to develop an optional mode which is essentially Ushaq. Ushaq is not actually part of the repertoire of Dastgah Mahur, what I am calling Ushaq is actually just the upper range of Mahur which is developed in gushe called by other names. The reference to Ushaq is more to relate this as closely as possible to Arabic music and terms. It depends on one’s interpretation whether to call it this or that. So you can either call the use of notes G A Bb C either upper range of Mahur, or as Ushaq. (I am open to other suggestions about this so please comment).

Ushaq/upper Mahur is used to return to Daad in the case of this maqam. Later on in Alizadeh’s introduction he plays bidaad and then jumps to the higher octave and continues to develop Homayoun which is the Dastgah which Bidaad is a part of. As mentioned above, Homayoun uses A quarter flat (koron). After Homayoun is expressed and developed, Alizadeh lands on G which allows for him to play Ushaq/upper Mahur and bring the melody back to Daad. This is what I call a “pivot note”. G is the pivot for which you can go from Homayoun to Mahur in this example. Likewise, when moving from Daad to Bidaad, D is the pivot note, and also the shahed (tonic/root). Another way to move from Homayoun into Daad is by resolving the Homayoun melody on F natural. F natural is one of the notes that introduces Homayoun melody, and also a concluding note for Homayoun.

The melodic development of Hossein Alizadeh’s Maqame Daad o Bidaad is thus:

Daad → Bidaad → Ushaq/Daad → Bidaad → Bidaad/Homayoun → Ushaq/Daad → Bidaad to conclude on D (shahed)

Listen to Hossein Alizadeh’s masterful rendition. It is rather haunting and something that not many people have heard before.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/117102855″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Conclusion

In Persian music, the Dastgah systems which I will write about in the future are made up of gushe or melodic niches. Daad is an example of a gushe which creates a modal quality where it shifts the root or tonic, and enunciates new notes in the scale. Bidaad is another gushe which creates a focal point on another note as well. The starting note of both gushes allow for some over lapping and creates a new maqam that has never been heard before.

Analysis of this maqam shows that modulation or changing from one scale to another one can be made possible at..

at the tonic/root (D is used to start Daad and is used to change to Bidaad)

at the pausing notes (F is a pausing note in Daad, so after playing Homayoun, you can conclude on F and then start playing Daad)

at the pivot notes (G is another concluding note in Homayoun and it also a perfect fourth degree from the tonic of Daad and Bidaad which is D, so G can be used to change from Homayoun to Daad and vice versa)

Another way to look at Maqam Daad o Bidaad is by use of Ajna:

Ushaq/Upper Mahur: G A Bb

Bidaad: B C D Eb

Homayoun: F G Ak(Koron) B C D Eb

If you have any thoughts or questions regarding this article please comment below. I would love to hear your ideas.

Did you enjoy this article? Get our latest articles in your email inbox!

[mc4wp-form]